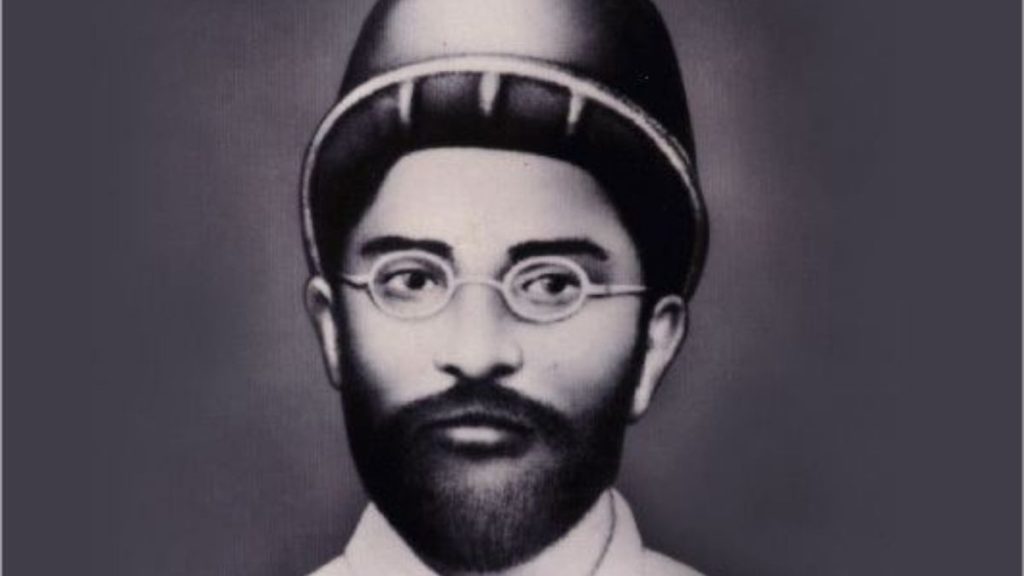

In the sweltering heat of late 19th-century Bombay, where the clamor of horse-drawn carriages mingled with the distant hum of British steamships, a young Parsi man named Ardeshir Burjorji Sorabji Godrej stood at a crossroads. Educated in the hallowed halls of law, he had the makings of a courtroom titan sharp-witted, principled, and from a family of means. Yet, by 1897, Ardeshir had traded his barrister’s wig for a blacksmith’s apron, hammering out the first indigenous locks in a modest shed on the fringes of the city. This pivot wasn’t born of caprice but of unyielding conviction: a refusal to bend to colonial whims and a burning desire to forge India’s self-reliance. What began as a quixotic quest against imported padlocks evolved into the Godrej Group, a sprawling conglomerate that today touches the lives of over a billion people worldwide, with a family fortune exceeding $16 billion. Ardeshir Godrej’s story is one of resilient ingenuity a testament to how one man’s moral compass could unlock an industrial empire.

Roots in a Changing Empire: A Parsi Upbringing

Ardeshir entered the world on April 13, 1868, as the firstborn of six children to Burjorji and Dosibai Godrej in the bustling port city of Bombay, then the jewel in Britain’s imperial crown. The Godrejs originally surnamed Gootherajee traced their lineage to prosperous Parsi traders who had fled Zoroastrian persecution in Persia centuries earlier, seeking sanctuary in India. By the time Ardeshir was born, his family had firmly planted roots in real estate, with his father and grandfather navigating the lucrative property markets fueled by the East India Company’s expansion. In a nod to their evolving identity, Burjorji formalized the family name as “Godrej” in January 1871, when Ardeshir was just three a subtle act of consolidation amid the cultural flux of colonial India.

Growing up in a Zoroastrian household steeped in ethics and enterprise, Ardeshir absorbed lessons of integrity and innovation from his Parsi heritage. The Parsis, a tight-knit community known for their philanthropy and business acumen, emphasized education and community service; figures like Jamsetji Tata exemplified this ethos, building institutions that outlasted empires. Young Ardeshir attended Elphinstone College, a prestigious institution favored by the British elite, where he honed his intellect. By his early twenties, he had set his sights on law, a profession that promised stability and influence in a land where justice often wore a colonial robe. In 1890, at age 22, he married Bachubai, an 18-year-old from a respected Parsi family, in a union that blended tradition with optimism. Tragically, Bachubai’s untimely death the following year, after a fateful outing to the Rajabai Clock Tower, left Ardeshir shattered, channeling his grief into a fierce determination to leave a mark on the world.

The Courtroom’s Bitter Lesson: Integrity Over Ambition

Armed with his law degree in 1894, Ardeshir launched into practice with the zeal of a reformer. His first major case took him to Zanzibar in East Africa, representing a prominent client against a British firm. The stakes were high: a dispute over surgical instruments, where Ardeshir’s side stood accused of substandard goods. In the courtroom, faced with pressure to embellish evidence or withhold inconvenient truths a common tactic in colonial litigation Ardeshir refused. “Truth is my only client,” he reportedly declared, echoing the Gandhian principles of satyagraha that were just beginning to stir in India. His candor cost him the case and the client’s trust; the firm dropped him mid-trial, stranding him in a foreign land with little more than his principles.

Returning to Bombay humbled but unbroken, Ardeshir tried his hand at local advocacy. Yet the profession’s ethical compromises clashed with his Zoroastrian upbringing, where “good thoughts, good words, good deeds” formed the creed. A newspaper article about surging crime rates in the city pickpockets preying on the unwary in crowded bazaars ignited a spark. Imported locks from British giants like Chubb dominated the market, their intricate mechanisms a symbol of colonial superiority, yet prone to rust in India’s humid climate and prohibitively expensive for the average household. Ardeshir saw an opportunity not just for profit, but for patriotism: Why should India rely on foreign keys to secure its homes? At 29, he abandoned law for locksmithing, borrowing funds from family friend Merwanji Cama to lease a 215-square-foot godown near the Bombay Gas Works. On May 7, 1897, in that unassuming shed in Lalbaug, the Godrej Brothers Company was born, with Ardeshir as the visionary tinkerer and his younger brother Pirojsha as the steadfast financier.

Forging Security: Innovations That Defied the Raj

Ardeshir’s early forays were far from smooth. His initial venture into manufacturing surgical tools floundered when a British partner balked at branding the products “Made in India.” Insisting on swadeshi pride self-reliance that would later fuel India’s independence movement Ardeshir walked away, undeterred. Turning to locks, he dissected imported models, identifying flaws like fragile springs that snapped in tropical heat. Months of trial and error in his dimly lit workshop yielded the “Anchor” lock in 1899: a sturdy, affordable contraption stamped with a bold guarantee of “unpickability.” To build trust, Ardeshir offered refunds for any breached lock a radical promise in an era of caveat emptor.

His breakthrough came in 1900 with the “Detector Lock,” inspired by Jeremiah Chubb’s 1818 design but adapted for Indian realities. This ingenious device alerted owners to tampering: an incorrect key triggered a hidden bolt, lockable only by the rightful one after a precise sequence. No special tools needed, just pure mechanical wit. Word spread like wildfire; jewelers, merchants, and even princely states clamored for Godrej’s wares. By 1901, Ardeshir expanded into safes, patenting fire-resistant models with seamless iron-sheet construction no welds to weaken under flames. These weren’t mere boxes; they were fortresses, priced accessibly to democratize security.

A pivotal alliance formed in 1902 when Merwanji Cama, grateful for past favors, introduced his nephew, Hormusji Boyce. Ardeshir welcomed the young engineer, renaming the firm Godrej & Boyce. Together, they refined production, incorporating Boyce’s precision engineering. Ardeshir’s travels to England’s Chubb factory in Wolverhampton demystified colonial tech; he returned not intimidated, but empowered, vowing to out-innovate the occupiers. His safes proved their mettle during Queen Mary’s 1911 visit to India, safeguarding royal jewels, and later in the 1944 Bombay dockyard blaze eight years after his death where Godrej vaults emerged unscathed amid devastation.

Yet Ardeshir’s ambitions stretched beyond metal. In 1918, he pivoted to soap-making, disturbed by animal fats in British brands that clashed with vegetarian Hindu and Parsi sensibilities. His vegetable-oil Cinthol soap became a household staple, blending hygiene with ethical innovation. Diversification continued: typewriters in the 1920s, door frames, and even early refrigerators, all under the Godrej banner of quality and nationalism.

Beyond Bolts: A Life of Quiet Revolution

Ardeshir’s personal life remained austere; he never remarried, pouring his energy into work and philanthropy. A teetotaler and vegetarian, he embodied simplicity, often cycling to the factory in threadbare clothes. In 1928, he briefly handed operations to Pirojsha to pursue farming, dreaming of sustainable agriculture, but returned when the venture faltered ever the pragmatist. His commitment to swadeshi aligned him with Gandhi; though not a frontline activist, Ardeshir’s factories employed thousands of Indians, fostering skills the British withheld.

An Enduring Legacy: Unlocking Billions

Ardeshir Godrej passed away on January 20, 1936, at 67, leaving no direct heirs but an indelible blueprint. Pirojsha’s sons Burjor, Sohrab, and Naval carried the torch, expanding into steel furniture, appliances, and real estate. Today, the Godrej Group, restructured in 2024 into Godrej Industries Group and Godrej Enterprises Group, spans consumer products (soaps, hair dyes), agrovet, properties, and aerospace boasting $5.7 billion in annual revenue and a family net worth topping $16.7 billion as of 2023. Under leaders like Adi Godrej, great-grandnephew and chairman, the empire innovates sustainably: mangrove preservation in Vikhroli’s 3,400-acre estate earned “green billionaire” nods, while aerospace engines powered India’s 2014 Mars mission.

Ardeshir’s legend endures not in opulence, but in the quiet click of a Godrej lock a reminder that true security begins with uncompromised truth. In an age of fleeting startups, his 128-year odyssey from a lawyer’s defeat to an industrial dynasty whispers: Principles, paired with persistence, unlock worlds.

Last Updated on Thursday, October 9, 2025 9:48 pm by Tamatam charan sai Reddy